Encounters: Lyotard & Monory

The recent exhibition at SPACE in Hackney evolved from the encounter of philosopher Jean-François Lyotard and painter-filmmaker Jacques Monory. Initiated by a letter from Lyotard, this eventually grew into decades of dynamic exchange.

An evening of film and discussion at L’Institut Français coincided with the exhibition, and included contributions from art historian Sarah Wilson, Herman Parret, editor of a new series of Lyotard’s writings on contemporary art, and philosopher Jonathan Lahey Dronsfield, who noted, ‘If I bear a responsibility as an artist, it is to the encounter’. The event paid belated homage to the reciprocal relations between renowned philosopher and – on Anglophone shores at least – lesser known artist. Dronsfield’s text plays out as a pronominal dialogue between a ‘me’ and a ‘him’ to consider what the nature of encounter between artist and thinker may be. Does art, as Lyotard suggests, place a demand on philosophy to come up with the words? Or does philosophy – note that Lyotard was against the term ‘theory’ – layer its own ideas onto the visual?

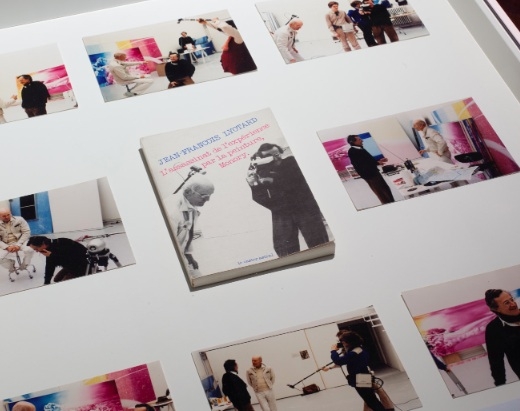

It was the work of Sarah Wilson in her book The Visual World of French Theory (2010) which brought SPACE curator Paul Pieroni’s attention to what he called ‘the propositional simplicity of philosopher meeting artist’ – in particular, to the rarely screened studio dialogue between the pair, which acts as the exhibition’s primary work (Premier Tournage, 1982). The film appealed not only for its setting – the spatial logic of the place-of-making, SPACE also provides studio space to artists – but for its seeming reversal of art’s ‘clamouring towards theory’, a predicament with which we are familiar today. For here, it is the philosopher who kneels at the feet of the artist.

Wilson evoked the intellectual climate of post-1968 France, where philosophers, including Deleuze and Guattari, Derrida and Althusser, forged contact with contemporary artists in such a way as to influence the formation of their concepts and positions. The ‘passions of the barricade’ became, as she noted, ‘“theory-based” radicalizations’ – a spirit of exchange that propelled work on both the canvas and in the notebook.

Many will be familiar with Lyotard, responsible for the announcement of ‘The Postmodern Condition’ in 1979, and the subsequent technology-embracing exhibition at the Centre Pompidou, Les Immatériaux (1985). Monory, an artist of the Narrative Figuration movement, which originated in France in the 1960s, has not however received any major exhibitions outside of continental Europe. In Monory’s images of Cadillacs and crime scenes, deserts and deserted villas, Lyotard saw the sexually charged structures of capitalism that would form the subject of his own Libidinal Economy in 1974.

Jacques Monory, Fuite n°3 (1980), oil on canvas

Theirs was a relationship that shook Lyotard’s writing beyond purely philosophical prose, as he saw Monory move freely between the media of painting, serigraph and film. Wilson noted that their playful book-work collaboration, Récits Tremblantes (Trembling Narratives, 1977), fragments of which are displayed alongside archival material in the exhibition, was produced quite literally on a faultline, ‘cavorting together as though on the cracks of an earthquake’, in the much-fantasized terrain of California. In Death Valley, Monory would paint both the desert and the stars, while Lyotard, witnessing satellite receivers decoding signals from above, would realize that space, through technology, had become a digital medium, drawing an arc from the romantic to the technological sublime.

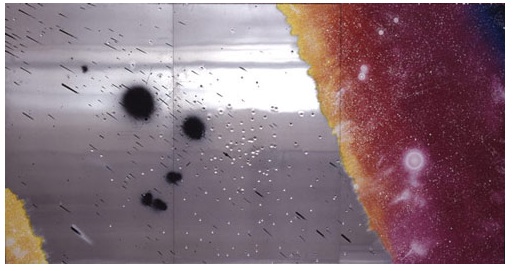

Jacques Monory, Ciel n°29 (1979), paint on metal

We are persuaded of Monory’s contemporaneity: where for Lyotard the painter’s fractured canvases, images-boxed-within-images, reflected the breakdown of grand narratives inherent to the Postmodern condition, today, his painting bursts with oily physicality at a moment at which the abstract digits of liberal capitalism fail to add up. The artist operates at a remove, framing multiple ‘screens’ – and all that conjures for both psychoanalysis and film theory – for image and viewer. Such consistently styled scenes take cues from detective fiction and film noir, spreads of magazines or girls’ legs, with the same distant yet prowling eye. In these images, Wilson finds ‘a burning coldness…[of] ice-floes, furs, inflexible mirrors shattered by gunshots… swimming pools of death.’ This is the chill of Deleuze’s Coldness and Cruelty (1971), Freud’s death drive painted blue – Monory’s default, mythologized hue. The blue-indigo wash of Brighton Belle (1974), one of the Monory shorts on display in the exhibition at SPACE, recalls the filters of after-dark screenings at the drive-ins he would frequent in his youth, both crepuscular and other-ing.

In contrast to this coldness, Premier Tournage presents a warm, human scenario – not adjectives associated with Lyotard’s writing – as Monory descends a white spiral staircase to greet his guest. But let’s not forget that the word ‘encounter’ also contains contra, against, and first signified a ‘meeting of adversaries’, a confrontation. In discussion, Dronsfield raised the question of tensions and misapprehensions between the pair. For if the film shows the philosopher as reverent, Lyotard equally projects onto the artist the idea that Monory too is un philosophe spontané, while Monory admitted elsewhere that he understands little of what Lyotard writes about him in The Assassination of Experience by Painting (1984). Present for the event at L’Institut Français, Monory sat silently on the front row; in dark shades and a leather jacket, he is now close to 80.

‘Lyotard & Monory: SCREENS’ showed that the relations between philosopher and artist do not simply course one way or another, neither an A to B influence, nor an over-reading into meaning. We saw concrete collaboration as well as miscommunication, intimacy as well as critical distance. ‘Every encounter is aleatory’ – this is Althusser, cited by Wilson – ‘not only in its origins, but also in its effects. Every encounter may not have taken place.’ The wilful spirit to seek out intellectual encounters in seventies France leads us to ask how much, and through which media and means, philosophy chooses to interact with art today.