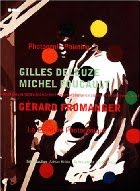

Photogenic Painting

Photogenic Painting

packages together a lengthy introduction and two essays by Deleuze and

Foucault on Gerard Fromanger, a French hyperrealist painter whom one of

the editors calls “

the

political artist of 1968 and its aftermath.” The volume also offers a

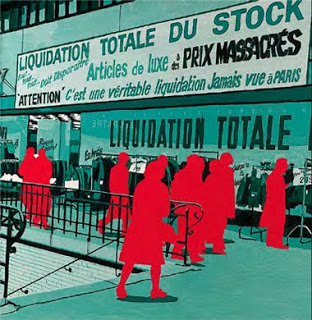

generous collection of images of Fromanger’s paintings, which are

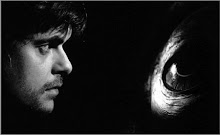

relatively unknown outside France. Fromanger was friends with the two

philosophers and painted magnificent portraits of them, as well as of

other French intellectuals, including Guattari and Sartre. Deleuze and

Foucault return the favor in their critical “portraits” of Fromanger,

sharpening their respective theoretical frameworks into supportive

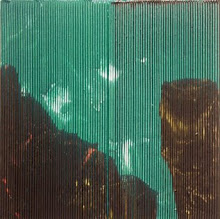

introductions to his work. Deleuze’s essay, “Cold and Heat,” is perhaps

a bit too abstract. Deleuze argues that “Fromanger’s model is the

commodity.” In the world Fromanger paints, everything has been

“rendered in the terms of the single model, the Commodity, which

circulates with the painter.”

Rather

than reject the model of the commodity, or attempt to criticize it from

supposed point of externality, Fromanger works wholly within the

“system of indifferences in which exchange-value circulates.” In his

paintings, he manipulates the relational potential of the hotness and

coldness of different colors, creating “connections,” ”disjunctions,”

and “conjunctions” between different elements of the paintings.

Deleuze praises this “mobilisation of indifferents” for its “radical

absence

of bitterness, of the tragic, of anxiety, of all this drivel you get in

the fake great painters who are called witnesses to their age.” He

concludes, “From what is ugly, repugnant, hateful and hateable he knows

how to bring out the colds and hots which produce a life for tomorrow.

We can imagine the cold revolution as having to heat the over-heated

world of today.”

Foucault’s

essay, “Photogenic Painting,” is the better contribution, a remarkably

clear and insightful text that makes one wish that Foucault would have

written more in the way of art criticism. Foucault’s argument is

especially relevant today, as images are increasingly remediated as they

circulate throughout digital networks. Foucault takes issue with the

modernist attempt to purify painting of everything but its own essence.

Instead, he finds inspiration in the early decades of photography, a

period when photographers playfully indulged in a wide variety of

“operations” on their images, many of which, such as painting directly

on the photographs, undermined the border between photography and

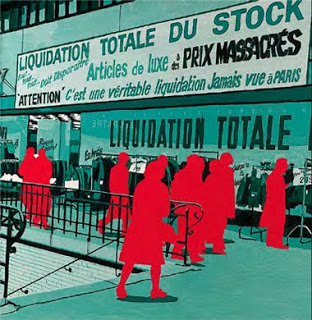

painting. Confronted today with political and commercial control over

images, we need to learn once again how to “put images into circulation,

to convey them, disguise them, deform them, heat them red hot, freeze

them, multiply them.” According to Foucault, “Pop Art and hyperrealism

have re-taught us the love of images. Not by a return to figuration,

not by a rediscovery of the object and its real density, but by plugging

us in to the endless circulation of images.” “Pop artists and

hyperrealists paint images,” but not images that are meant to accurately

represent reality. These images are “relays” that transmit

photographic images, further circulating them in a form that retains the

traces of this act of translation and circulation between media.

Foucault considers Fromanger an exemplary hyperrealist who is ahead of

the game. Fromanger creates a painting by taking a photo, projecting

this photo on the canvas, and then directly painting over the projected

image. His photos are not deliberately composed, but rather record a

“photo-event.” According to Foucault, Fromanger attempts “To create a

painting-event on the photo-event. To generate an event that transmits

and magnifies the other, which combines with it and gives rise, for all

those who come to look at it, and for every particular gaze that comes

to rest on it, to an infinite series of new passages.” When the

photographic projection is turned off, the painting must “sustain” the

image; its function is not to fix the image once and for all, but to

help it to continue to circulate, beyond the original photograph. “The

function of the photo-slide projection-painting sequence present in

every painting is to ensure the transit of an image. Each painting is a

thoroughfare; a ‘snap’ which rather than fixing the movement of things

in a photograph, animates, concentrates and magnifies the movement of

the image through its successive supporting media.” Fromanger can

therefore take a single photograph, a single photographic event, and

relay its image in different ways through a series of paintings.

Foucault concludes, “We are now coming out of the long period during

which painting always minimized itself as painting in order to ‘purify’

itself, to sharpen and intensify itself as art. Perhaps with the new

‘photogenic’ painting it is at last coming to laugh at that part of

itself which sought the intransitive gesture, the pure sign, the

‘trace’. Here it agrees to become a thoroughfare, an infinite

transition, a busy and crowded painting. And in opening itself up to so

many events that it relaunches, it incorporates all the techniques of

the image: it re-establishes its relationship with them, to connect to

them, to amplify them, to multiply them, to disturb them or deflect

them.”

Photogenic Painting

packages together a lengthy introduction and two essays by Deleuze and

Foucault on Gerard Fromanger, a French hyperrealist painter whom one of

the editors calls “the

political artist of 1968 and its aftermath.” The volume also offers a

generous collection of images of Fromanger’s paintings, which are

relatively unknown outside France. Fromanger was friends with the two

philosophers and painted magnificent portraits of them, as well as of

other French intellectuals, including Guattari and Sartre. Deleuze and

Foucault return the favor in their critical “portraits” of Fromanger,

sharpening their respective theoretical frameworks into supportive

introductions to his work. Deleuze’s essay, “Cold and Heat,” is perhaps

a bit too abstract. Deleuze argues that “Fromanger’s model is the

commodity.” In the world Fromanger paints, everything has been

“rendered in the terms of the single model, the Commodity, which

circulates with the painter.”

Photogenic Painting

packages together a lengthy introduction and two essays by Deleuze and

Foucault on Gerard Fromanger, a French hyperrealist painter whom one of

the editors calls “the

political artist of 1968 and its aftermath.” The volume also offers a

generous collection of images of Fromanger’s paintings, which are

relatively unknown outside France. Fromanger was friends with the two

philosophers and painted magnificent portraits of them, as well as of

other French intellectuals, including Guattari and Sartre. Deleuze and

Foucault return the favor in their critical “portraits” of Fromanger,

sharpening their respective theoretical frameworks into supportive

introductions to his work. Deleuze’s essay, “Cold and Heat,” is perhaps

a bit too abstract. Deleuze argues that “Fromanger’s model is the

commodity.” In the world Fromanger paints, everything has been

“rendered in the terms of the single model, the Commodity, which

circulates with the painter.” Rather

than reject the model of the commodity, or attempt to criticize it from

supposed point of externality, Fromanger works wholly within the

“system of indifferences in which exchange-value circulates.” In his

paintings, he manipulates the relational potential of the hotness and

coldness of different colors, creating “connections,” ”disjunctions,”

and “conjunctions” between different elements of the paintings.

Deleuze praises this “mobilisation of indifferents” for its “radical absence

of bitterness, of the tragic, of anxiety, of all this drivel you get in

the fake great painters who are called witnesses to their age.” He

concludes, “From what is ugly, repugnant, hateful and hateable he knows

how to bring out the colds and hots which produce a life for tomorrow.

We can imagine the cold revolution as having to heat the over-heated

world of today.”

Rather

than reject the model of the commodity, or attempt to criticize it from

supposed point of externality, Fromanger works wholly within the

“system of indifferences in which exchange-value circulates.” In his

paintings, he manipulates the relational potential of the hotness and

coldness of different colors, creating “connections,” ”disjunctions,”

and “conjunctions” between different elements of the paintings.

Deleuze praises this “mobilisation of indifferents” for its “radical absence

of bitterness, of the tragic, of anxiety, of all this drivel you get in

the fake great painters who are called witnesses to their age.” He

concludes, “From what is ugly, repugnant, hateful and hateable he knows

how to bring out the colds and hots which produce a life for tomorrow.

We can imagine the cold revolution as having to heat the over-heated

world of today.” Foucault’s

essay, “Photogenic Painting,” is the better contribution, a remarkably

clear and insightful text that makes one wish that Foucault would have

written more in the way of art criticism. Foucault’s argument is

especially relevant today, as images are increasingly remediated as they

circulate throughout digital networks. Foucault takes issue with the

modernist attempt to purify painting of everything but its own essence.

Instead, he finds inspiration in the early decades of photography, a

period when photographers playfully indulged in a wide variety of

“operations” on their images, many of which, such as painting directly

on the photographs, undermined the border between photography and

painting. Confronted today with political and commercial control over

images, we need to learn once again how to “put images into circulation,

to convey them, disguise them, deform them, heat them red hot, freeze

them, multiply them.” According to Foucault, “Pop Art and hyperrealism

have re-taught us the love of images. Not by a return to figuration,

not by a rediscovery of the object and its real density, but by plugging

us in to the endless circulation of images.” “Pop artists and

hyperrealists paint images,” but not images that are meant to accurately

represent reality. These images are “relays” that transmit

photographic images, further circulating them in a form that retains the

traces of this act of translation and circulation between media.

Foucault considers Fromanger an exemplary hyperrealist who is ahead of

the game. Fromanger creates a painting by taking a photo, projecting

this photo on the canvas, and then directly painting over the projected

image. His photos are not deliberately composed, but rather record a

“photo-event.” According to Foucault, Fromanger attempts “To create a

painting-event on the photo-event. To generate an event that transmits

and magnifies the other, which combines with it and gives rise, for all

those who come to look at it, and for every particular gaze that comes

to rest on it, to an infinite series of new passages.” When the

photographic projection is turned off, the painting must “sustain” the

image; its function is not to fix the image once and for all, but to

help it to continue to circulate, beyond the original photograph. “The

function of the photo-slide projection-painting sequence present in

every painting is to ensure the transit of an image. Each painting is a

thoroughfare; a ‘snap’ which rather than fixing the movement of things

in a photograph, animates, concentrates and magnifies the movement of

the image through its successive supporting media.” Fromanger can

therefore take a single photograph, a single photographic event, and

relay its image in different ways through a series of paintings.

Foucault concludes, “We are now coming out of the long period during

which painting always minimized itself as painting in order to ‘purify’

itself, to sharpen and intensify itself as art. Perhaps with the new

‘photogenic’ painting it is at last coming to laugh at that part of

itself which sought the intransitive gesture, the pure sign, the

‘trace’. Here it agrees to become a thoroughfare, an infinite

transition, a busy and crowded painting. And in opening itself up to so

many events that it relaunches, it incorporates all the techniques of

the image: it re-establishes its relationship with them, to connect to

them, to amplify them, to multiply them, to disturb them or deflect

them.”

Foucault’s

essay, “Photogenic Painting,” is the better contribution, a remarkably

clear and insightful text that makes one wish that Foucault would have

written more in the way of art criticism. Foucault’s argument is

especially relevant today, as images are increasingly remediated as they

circulate throughout digital networks. Foucault takes issue with the

modernist attempt to purify painting of everything but its own essence.

Instead, he finds inspiration in the early decades of photography, a

period when photographers playfully indulged in a wide variety of

“operations” on their images, many of which, such as painting directly

on the photographs, undermined the border between photography and

painting. Confronted today with political and commercial control over

images, we need to learn once again how to “put images into circulation,

to convey them, disguise them, deform them, heat them red hot, freeze

them, multiply them.” According to Foucault, “Pop Art and hyperrealism

have re-taught us the love of images. Not by a return to figuration,

not by a rediscovery of the object and its real density, but by plugging

us in to the endless circulation of images.” “Pop artists and

hyperrealists paint images,” but not images that are meant to accurately

represent reality. These images are “relays” that transmit

photographic images, further circulating them in a form that retains the

traces of this act of translation and circulation between media.

Foucault considers Fromanger an exemplary hyperrealist who is ahead of

the game. Fromanger creates a painting by taking a photo, projecting

this photo on the canvas, and then directly painting over the projected

image. His photos are not deliberately composed, but rather record a

“photo-event.” According to Foucault, Fromanger attempts “To create a

painting-event on the photo-event. To generate an event that transmits

and magnifies the other, which combines with it and gives rise, for all

those who come to look at it, and for every particular gaze that comes

to rest on it, to an infinite series of new passages.” When the

photographic projection is turned off, the painting must “sustain” the

image; its function is not to fix the image once and for all, but to

help it to continue to circulate, beyond the original photograph. “The

function of the photo-slide projection-painting sequence present in

every painting is to ensure the transit of an image. Each painting is a

thoroughfare; a ‘snap’ which rather than fixing the movement of things

in a photograph, animates, concentrates and magnifies the movement of

the image through its successive supporting media.” Fromanger can

therefore take a single photograph, a single photographic event, and

relay its image in different ways through a series of paintings.

Foucault concludes, “We are now coming out of the long period during

which painting always minimized itself as painting in order to ‘purify’

itself, to sharpen and intensify itself as art. Perhaps with the new

‘photogenic’ painting it is at last coming to laugh at that part of

itself which sought the intransitive gesture, the pure sign, the

‘trace’. Here it agrees to become a thoroughfare, an infinite

transition, a busy and crowded painting. And in opening itself up to so

many events that it relaunches, it incorporates all the techniques of

the image: it re-establishes its relationship with them, to connect to

them, to amplify them, to multiply them, to disturb them or deflect

them.”